SUMMARY: Tullow discovered oil in Turkana, but stalled production led them to sell their assets to Gulf Energy for Ksh. 15.5B and exit the market. This article explains why and how.

In this article:

Background and Context

Tullow's Kenyan Journey

The Pipeline Problem

Tullow Decides to Exit

Finding a Buyer

Gulf Energy’s Play

Deal Terms & conditions

The Real Bottleneck (FDP Vs. FID)

Final Thought

BACKGROUND & CONTEXT

In the 2000s, Kenyans barely talked about oil. We didn’t have any.

Tullow Oil operations in Turkana (Image credit: Citizen Digital)

But geologists had long suspected that the East African Rift System, the same geological feature running from Mozambique to Ethiopia, could hold hydrocarbons.

Unfortunately, oil exploration is extremely risky and expensive.

You can drill several wells, spend millions of dollars, and still find nothing.

To manage risk, governments typically carve their territories into “blocks” and invite specialist explorers to take the gamble.

In northern Kenya, these blocks were opened up in the 2000s, and companies bid for the rights to search for oil.

These exploration rights are typically in the form of Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs).

A PSC basically says:

You (company) explore at your own cost and your own risk.

If you discover oil, the state keeps ownership of the oil.

You are allowed to recover your expenses from future production.

After cost recovery, we share the profits.

In simple terms: explorers take the risk; governments keep the sovereignty.

Tullow Oil, a London-based company that searches for oil and develops oil projects mainly in Africa, secured the exploration rights from the Kenyan government.

They were a strong fit because:

They had discovered oil in Uganda’s Lake Albert region

Their business model was “frontier exploration, prove resource, sell or farm down”

They were willing to take risks that larger oil companies avoided

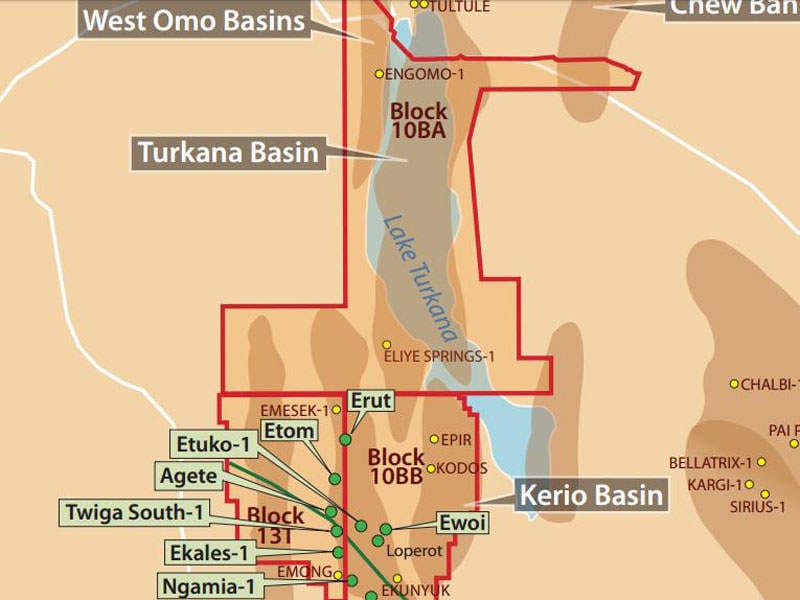

By 2010–2011, they had taken over blocks 10BB and 13T in Turkana through partnerships and acquisitions.

TULLOW’S KENYAN JOURNEY

Tullow Oil did not arrive in Kenya by accident. They were specialists in frontier exploration, operating where larger oil explorers feared to go.

Tullow offices in Turkana, near the Ngamia 8 well. (Image credit: Business Daily)

They had taken risks in Ghana, Uganda, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mauritania, and been rewarded with major finds.

Kenya was the next frontier.

In 2012, after years of seismic studies and exploratory drilling, Tullow struck oil at Ngamia-1 in Lokichar.

This was not a small discovery.

The well was productive,

the flow rate was promising,

and for the first time in history, Kenya had a commercially viable basin.

Initial resource estimates ranged up to 560 million barrels (2C), though the latest plan submitted under Gulf Energy targets about 326 million barrels for the first development phase.

But oil discoveries are not oil wealth.

They are only invitations to spend massive amounts of money, first to understand the basin, then to build the infrastructure to extract and transport the crude.

Turning early discoveries into large-scale production proved far more complicated for Tullow and their partners.

THE PIPELINE PROBLEM

The Lokichar oil is waxy and thick, it has to be heated as it moves. That requires special pipeline design, more power, and higher construction costs.

Image credit: Minbane

For the oil to reach global markets, Kenya needed a heavily engineered, heated pipeline stretching hundreds of kilometers to the coast.

This pipeline was the heart of the project, but it was also the biggest headache.

Engineering firms quoted nearly $2 billion for the line alone.

Financiers balked at the cost.

Insurance premiums were high because of community tensions and political instability.

And Kenya’s government, already under fiscal strain, could not offer the sovereign guarantees lenders demanded.

Without this pipeline, the project could not reach FDP (Field Development Plan) approval or FID (Final Investment Decision).

And without either of these, the project was no longer viable.

The pipeline issue, along with several other difficulties, pushed Tullow to make the decision to leave.

TULLOW DECIDES TO EXIT

By the mid-2010s, the ground had shifted under the entire oil industry, and the Kenya project moved from “frontier opportunity” to “financial strain.”

Former energy CS Charles Keter and Tullow’s Martin Mbogo at the 2017 crude oil pipeline signing. (Image Credit: Business Daily)

Unfortunately for Tullow, a few big problems hit them at the same time.

1. The Oil Price Crash Changed Everything

In 2014–2016, global oil prices fell from over US$100 to under US$40.

Suddenly, multi-billion-dollar frontier projects like Turkana no longer made commercial sense.

Investors wanted quick, low-cost barrels, not complex fields in remote basins that needed a heated export pipeline.

2. Tullow’s Debt Ballooned

At the same time, Tullow was dealing with heavy corporate debt, peaking around US$1.5 billion.

Debt service squeezed their ability to fund new projects.

From the board’s perspective, every dollar spent in Kenya was a dollar not used to stabilise the company.

3. ESG Pressure Closed Doors to Financing

By the late 2010s, global banks and insurers began pulling back from long-term fossil fuel projects.

Heated pipelines, remote fields, large environmental footprints, these were “red flags.”

This meant that even if the project was technically sound, the financing environment had become extremely hostile.

4. Kenya’s Approvals Moved Slower Than Investors Expected

The Field Development Plan (FDP) and upstream agreements took years to progress.

Land issues, pipeline routing questions, and shifting government priorities created uncertainty.

For lenders, uncertainty equals delay, and delay equals risk.

5. The Funding Gap Became Too Big to Bridge

By the time all partners tallied the numbers, Turkana needed US$5–7 billion to reach full production.

In a high-cost, hard-to-finance, ESG-pressured environment, raising that capital became nearly impossible for a mid-sized explorer like Tullow.

6. Partners Pulled Back, Leaving Tullow Carrying the Load

TotalEnergies and Africa Oil gradually reduced their involvement, leaving Tullow with more risk on its balance sheet. The dream of a strong consortium faded.

One of the Tullow oil wells in Turkana (Image credit: Business Daily)

Faced with these pressures, exit became the only sensible move.

By 2023, Tullow wasn’t just struggling in Kenya, it was restructuring globally.

In fact, by 2025, they had already started selling off several non-core assets elsewhere (such as in Gabon) to raise cash and reduce exposure.

Kenya, with its massive capital requirements and long timelines, simply didn’t fit the new strategy.

So the company made a pragmatic decision to stop trying to push a mega-project uphill, and instead hand it to a player with a higher risk appetite.

FINDING A BUYER

This was a risky project, and Tullow knew it wouldn’t be easy to find a buyer. Anyone stepping in would need the balance sheet, and the appetite, to shoulder years of uncertainty.

Of the handful of regional firms that could handle this risk, Gulf Energy emerged as that partner.

Gulf is a Kenyan company involved in various operations including retail fuel sales, petroleum product trading, and power generation.

As experienced as they are, Gulf understood the risks clearly. But they also saw the long-term upside if the project could be revived and eventually reach production.

GULF ENERGY’S PLAY

At first glance, it looks counterintuitive. Tullow is exiting after years of sunk costs and frustration, while Gulf is entering the same project.

A Gulf Energy Petrol station (Image credit: hapakenya)

But the energy firm isn't isn’t stepping into the same problem Tullow had.

It’s stepping in at a different price, different time, and with a different agenda.

There are two main factors that made this deal too good to pass up, despite it's troubles.

1. The Price vs. Value Gap

Tullow spent over US$2 billion across exploration and appraisal in Kenya. Gulf is reportedly buying the same assets for about US$120 million.

That’s a massive discount. Less than 10 cents on the dollar of Tullow’s original investment.

So, even though the project carries risk, Gulf is:

Entering at the bottom of the cycle, after Tullow has absorbed the exploration risk.

Acquiring proven assets (these aren’t speculative, they’re discovered resources with confirmed reserves).

Paying a performance-linked price, not an upfront lump sum. Which means it only pays more if the project progresses.

Even if it never produces at massive scale, owning the license is a strategic asset that can be monetized in multiple ways, including:

Bringing in new partners,

Selling part of their stake to reduce risk,

Using the asset to secure loans, or

Selling the whole project to a big oil company later if it grows.

2. Vertical intergration

From their side, this deal is not really about short-term profit.

It’s a foothold into upstream oil, the “source” of energy, which complements their existing midstream (distribution) and downstream (retail) businesses.

They already trade, transport, and distribute oil.

Now, by entering exploration and production, they can:

Control more of the value chain (from well to pump).

Secure local energy supply, especially as Kenya aims to be energy self-sufficient.

Position for future regional energy politics (South Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania pipelines, etc.).

This is a vertical integration move, common among ambitious African energy players trying to build regional dominance.

DEAL TERMS & CONDITIONS

Because of how risky the project is, Gulf needed a structure that protected their own interests while giving Tullow a clean exit.

Image credit: Tullow Oil

The two sides negotiated a deal that balanced ambition with caution on both sides.

Heres how the deal was structured:

1. Three Tranches Linked to Project Milestones

Tullow is selling 100% of its Kenyan assets (Blocks 13T and 10BB in the South Lokichar Basin) to Gulf Energy through a phased acquisition.

Gulf does not pay everything upfront. Instead, payments are tied to the project’s progress toward commercialisation.

Tranche 1 — On Signing (~USD 10–15M)

Gulf pays a small entry payment when the deal closes.

This gives them operational control and ownership of Tullow’s on-the-ground assets.

This is the least risky tranche for Gulf.

Tranche 2 — On Final Investment Decision (FID) (~USD 50M+)

This is paid only if the project reaches Final Investment Decision (FID), meaning the pipeline, financing, and development plan are officially approved.

This tranche is the toughest hurdle.

Kenya’s oil has struggled to reach FID for 10+ years.

If it never happens, Gulf does not pay this tranche.

Tranche 3 — On First Oil (~USD 100M–150M)

This is paid only when oil actually starts flowing through the pipeline.

This aligns with global oil deal structures where major payments come at production.

Gulf only pays when commercial risk has dropped to near zero.

In short: Gulf only deploys serious capital if the project becomes real.

2. Carry Structure: Gulf Pays Some Costs on Behalf of Others

Gulf is offering a carried interest arrangement, meaning they will pay certain early development costs on behalf of the Government of Kenya (10% carried interest)

These costs are only recoverable from future oil revenues.

So, if the project fails, Gulf loses the carried amounts.

This significantly derisks the Government’s participation and makes the deal more politically palatable.

3. Royalty and Fiscal Terms

Kenya retains:

A 10% government carried interest

Royalties on gross production as defined in the PSC

Cost recovery limits (typically 60–70% in Kenyan PSCs)

Profit oil sharing based on production levels

Gulf inherits these obligations; they do not change.

Kenya’s revenue only flows after cost recovery, so Gulf’s ability to fund the pipeline and development plan matters directly to Treasury.

4. Tullow Retains a Royalty Interest in Future Oil

Instead of a clean exit, Tullow has structured the deal so it earns a future royalty override on production.

This means Tullow still benefits if, but only if, the project succeeds.

It aligns Tullow’s interests with Gulf’s success.

It also gives Tullow a seat at the table without incurring future costs.

This is common in frontier oil exits where the seller still wants upside.

5. Operator Transition and Project Control

Gulf takes over as operator of the South Lokichar development project.

All staff, data, licenses, seismic data, and local obligations transfer to Gulf.

Gulf becomes responsible for:

negotiating pipeline terms

securing financing

managing field development

environmental & community relations

This transition is significant, as operatorship is where the real strategic power lies.

6. Total Deal Value (If All Milestones Are Reached)

While the exact numbers depend on negotiations, publicly available structures suggest:

Total potential deal value: USD 150–250 million

Actual payments will depend 100% on:

reaching FID,

constructing the pipeline,

producing first oil.

This is why analysts call it a “contingent acquisition”.

THE REAL BOTTLENECK: FDP Vs. FID

Before any oil project can move from “exciting discovery” to “actual production,” it must pass through two critical approvals.

A geographical map of the plan

These approvals are called the Field Development Plan (FDP) and the Final Investment Decision (FID).

And in the entire 14-year Turkana story, these two have been the biggest chokepoints.

They sound technical, but they’re really just formal checkpoints that answer two simple questions:

Is the engineering plan ready?

Is the financing committed?

The two terms (FDP and FID) sound similar but they mean very different things in the life cycle of an oil (or major infrastructure) project.

Here’s a simple breakdown of both:

1. FDP = Field Development Plan

An FDP (Field Development Plan) shows what will be built and how much it will cost.

It is a technical and commercial blueprint for how a discovered oil field will be developed.

Think of it as the master plan.

What it contains:

Estimated recoverable reserves

Well design & drilling schedule

Surface facilities design (CPF, gathering systems)

Pipeline routing

Environmental & social impact assessments

Cost estimates (CapEx + OpEx)

Economic modelling

Local content commitments

Timelines

Who prepares it:

The oil company/consortium.

Who approves it:

The government (e.g., Ministry of Energy, EPRA, NEMA, etc.).

Purpose:

To prove to the government that the project is technically sound, environmentally acceptable, and potentially commercially viable.

2. FID = Final Investment Decision

An FID (Final Investment Decision) approves the money needed to actually build what the FDP approved.

It is the go/no-go decision by investors and project sponsors to commit billions of dollars to develop the field.

It means:

“We have financing, all approvals, contracts, guarantees, and infrastructure lined up… we are ready to spend the money.”

What it requires to be in place:

Approved FDP

Signed oil pipeline agreements

Financing secured (banks, equity partners, DFIs)

Government guarantees and fiscal terms

Land access and community agreements

Environmental permits

Commercial contracts (EPC, drilling rigs, O&M)

Economics that actually make sense (NPV/IRR > hurdle rate)

Who makes this decision:

The investors + consortium partners (e.g., Tullow, Total, Africa Oil, Gulf Energy).

Purpose:

It triggers the actual release of capital, moving the project from planning to construction.

3. Why Turkana Never Reached FDP and FID

An FDP comes before FID. FDP approval is necessary but not sufficient for FID.

Over the years, Tullow submitted multiple versions of the FDP.

The Kenyan government approved the revised FDP in 2023. But despite the early excitement, the project hit the same bottlenecks over and over:

The pipeline alone needed US$2–3 billion in funding.

Field development required another US$3–4 billion.

Oil prices crashed in 2014–2016.

Tullow entered a debt crisis.

ESG pressures limited international financing.

Kenya struggled to coordinate approvals and infrastructure timelines.

It became nearly impossible for Tullow to secure the consortium of lenders needed for FID. And without FID in sight, the FDP also stalled, because no one approves a plan they can’t fund.

FINAL THOUGHT

The Tullow-Gulf Energy deal shows mastery in balancing risk exposure with strategic positioning, but there's a caveat.

Image credit: Tullow Oil

At first, it may appear as if all three major parties got what they wanted.

Tullow de-risks its balance sheet and avoids political friction in Kenya.

Gulf buys into a potentially transformational project with government support (and maybe concessional financing later).

Kenya keeps local equity in a politically sensitive sector, avoiding backlash.

It’s easy to admire the structure, but the real test is operational.

The Lokichar project has failed to reach Final Investment Decision (FID) for a decade. The pipeline, financing, and environmental hurdles remain huge.

If Gulf and its partners can finally reach FID, that will be the true validation of the structure.

Until then, it remains a masterclass on paper; brilliant design, uncertain execution.