When President William Ruto took office in 2022, Kenya was drowning in debt (sh8.6 trillion), many government-owned companies were making losses, while others were riddled with corruption and outdated infrastructure.

The news has been covered by most major media outlets, including The Business Daily.

To raise money, instead of borrowing more or raising taxes, Ruto opted to sell assets like KICC. This decision has come with shock, public outrage, and emotional backlash.

In this article:

The Thinking Behind Ruto’s Decision to Sell

What Exactly is “Privatization“?

A Brief History of Kenya’s Privatization Act

What’s on the Auction Block?

Three Dangers of Privatization

Public Backlash & What’s at Stake

Consequences for Construction and Infrastructure Firms

The Road Ahead

THE THINKING BEHIND RUTO’S DECISION TO SELL

Ruto’s privatization plan is based on a simple logic: “We’re deep in debt and out of cash. Let’s sell underperforming companies to private investors, use that money to pay down debt, and get the economy back on track.”

Kenya’s sh10.3 trillion ($79billion) debt load is one of the highest in sub-Saharan Africa, and leaves the government with little room to maneuver.

More than KSh 1.8 trillion ($13.8 billion) is needed each year just to service existing loans. That’s close to half of the national budget.

The country spends more money repaying loans than funding schools or hospitals.

As a result, there is growing pressure to either raise taxes, cut spending, or find new sources of revenue, and quickly.

Ruto’s solution for raising money fast was to privatize 248 government-owned businesses.

KICC was one of the first 11 assets up for sale.

The president’s playbook is built on 3 big beliefs:

Private companies run things better. They have skin in the game and care about efficiency.

The government should focus on policy, not business. Let the private sector build and operate, the government should regulate and tax.

Kenya is broke. Asset sales are a quick way to raise cash without raising taxes or borrowing more.

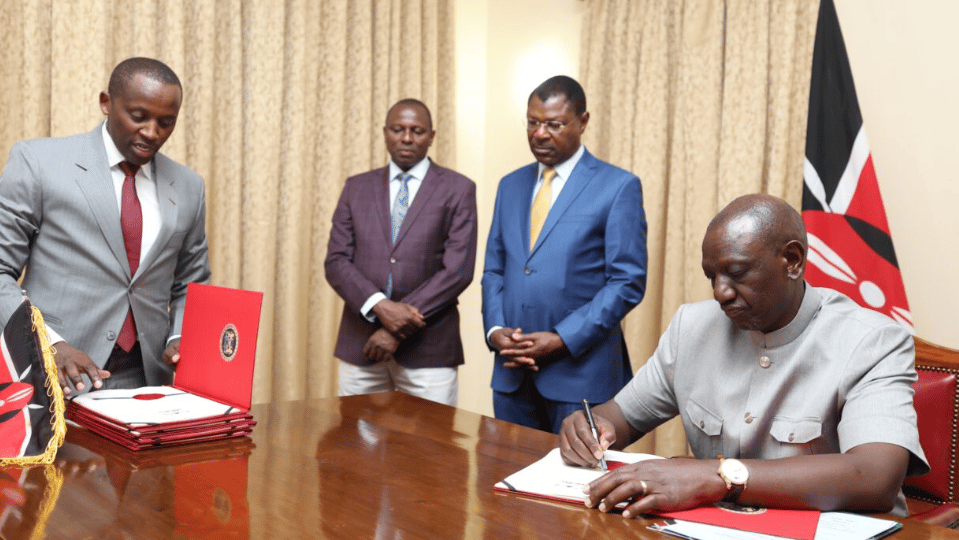

By replacing the 2005 law, the 2023 Act makes it quicker and easier to sell state-owned assets. [Image credit: Nation Media Group]

To make these sales quick and easy, his administration pushed through the Privatization Act of 2023 which allowed them to skip some of the usual government checks.

Essentially, this act was a legal shortcut to speed up asset sales.

It also matched his economic plan and had support from international lenders like the IMF, who often encourage governments to sell state-owned businesses to cut spending.

By privatizing these assets, the Kenyan government hoped to raise between Ksh60 billion ($463 million) and Ksh110 billion ($849 million), less than 1% of Kenya’s total debt.

WHAT EXACTLY IS “PRIVATIZATION“?

Governments, like households, own a lot of stuff. And over time, some of that stuff becomes a burden.

Kenya Railways Corporation recently reported a Sh50.37 billion deficit in the financial year ending June 2024. [Image Credit: Business Daily]

For example:

A sugar factory that's always in debt.

A port that's mismanaged.

A power company that bleeds billions.

As these government-run businesses (called state corporations or parastatals) keep losing money year after year, taxpayers end up footing the bill.

To manage the situation, governments sometimes adopt a strategy known as “Privatization”.

In simple terms, privatization means selling these state-owned businesses or properties to private companies or individuals.

Governments do this to:

Raise quick money (liquidity)

Reduce losses from inefficient or corrupt public firms

Shift management to the private sector, which is often seen as more efficient

Liking this so far? Don't miss out on future deep dives, subscribe now!

A BRIEF HISTORY OF KENYA’S PRIVATIZATION ACT

Kenya already had a law on privatization, the Privatization Act of 2005. However, it was slow and complicated.

In the 2005 version:

Every sale needed multiple approvals

Parliament had to be involved at every step

The process dragged on for years

As a result, only one company was ever sold using that law, the Safaricom IPO in 2008.

The Privatization Act of 2023 replaced the old law to make things faster and more efficient, but was also more prone to exploitation.

Key 2023 changes included:

Giving the Treasury more direct control over which companies to sell

Removing Parliament from the approval process (they’d only be informed)

Creating a new Privatization Authority to oversee everything

In short: the law streamlined the process, allowing the government to sell assets quickly, even without full public or legislative debate.

As of today, June 17th 2025, Kenya has paused implementation of the 2023 Privatization Act and reverted to the Privatization Act of 2005.

WHAT’S ON THE AUCTION BLOCK?

Some of the 248 assets slated for sale were to be sold completely. Others were to be partially privatized. For example, the government keeps 40%, sells 60%.

Some government-owned companies that have become financial burdens include:

Kenya Railways:

Despite spending over Sh327 billion on the Standard Gauge Railway, it still runs at a loss and requires ongoing subsidies.

Kenya Power Lighting Company (KPLC):

Struggling with power theft and bad contracts, it posted a Sh3.19 billion loss in 2022 and has needed repeated bailouts.

Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC):

The national broadcaster is weighed down by Sh7.5 billion in debt, outdated infrastructure, and low revenues.

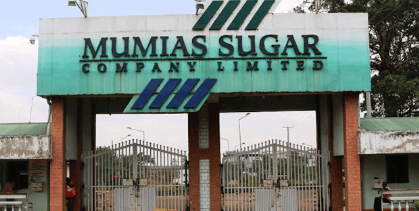

Mumias Sugar:

Collapsed after years of mismanagement; it received billions in bailouts before going into receivership.

Of all the evaluated companies, these were the ones listed for sale:

Kenya Pipeline Company (KPC)

Kenya Ports Authority

Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen)

National Oil Corporation

Mumias and Nzoia Sugar factories

Government-owned hotels, banks, and real estate

Don’t miss our next analysis, subscribe to get it straight in your inbox.

P.S.

A big part of my day job is helping mid-sized Engineering & Construction firms figure out why their growth has stalled. The symptoms are often clear, but the root causes are usually hidden.

Over time, we built a structured framework (The E&C Growth Index) to quickly uncover bottlenecks across 5 critical business areas. If you're curious what's holding your firm back, take the test. You'll get a personalized report in under 5 minutes, straight to your inbox.